It's not 'us versus them' or even 'us on behalf of them.' For a design thinker, it has to be 'us with them'

Tim Brown, co-founder and CEO of IDEO

Updated on Feb 27, 2026

·

13 min read

Design thinking gets mentioned in job descriptions, workshops, and product roadmaps—but what does it actually mean in practice?

In this article, we’ll walk through the basics of design thinking, its five stages, where teams usually get stuck, and how different frameworks all point to the same core logic. If you’re looking for a clear, practical overview you can apply to real projects, this is for you.

Design thinking is a problem-solving approach built on creating empathy with users, generating ideas, prototyping, and testing those prototypes with the target audience.

The goal is to create solutions that are useful, feasible, and sustainable. It’s an iterative, non-linear process where we don’t get attached to ideas and quickly adapt based on feedback.

Design thinking makes concepts and methods familiar to designers more accessible to non-designers, and it can be used to solve any type of problem — even those where the outcome isn’t a digital product. It’s an open, flexible, iterative, interdisciplinary, and user-focused methodology.

Design thinking is especially useful for confusing or unknown "wicked" problems, a concept introduced by Horst Rittel in the 1960s and formalized with Melvin Webber in their 1973 paper. Wicked problems are messy, complex problems with no single right answer, which later became essential to design thinking.

Modern design thinking has roots in 20th-century developments in design methods, systems thinking, and management science, especially in response to complex post-war technological and organizational challenges.

In 1992, Richard Buchanan linked design thinking and wicked problems, positioning design thinking as a way to merge knowledge from separate, specialized disciplines.

In 2004, David Kelley co-founded the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford, commonly known as the d.school, making design thinking a central practice in education and innovation.

Today, design thinking is widely used in universities, business schools, and companies as a leading innovation methodology.

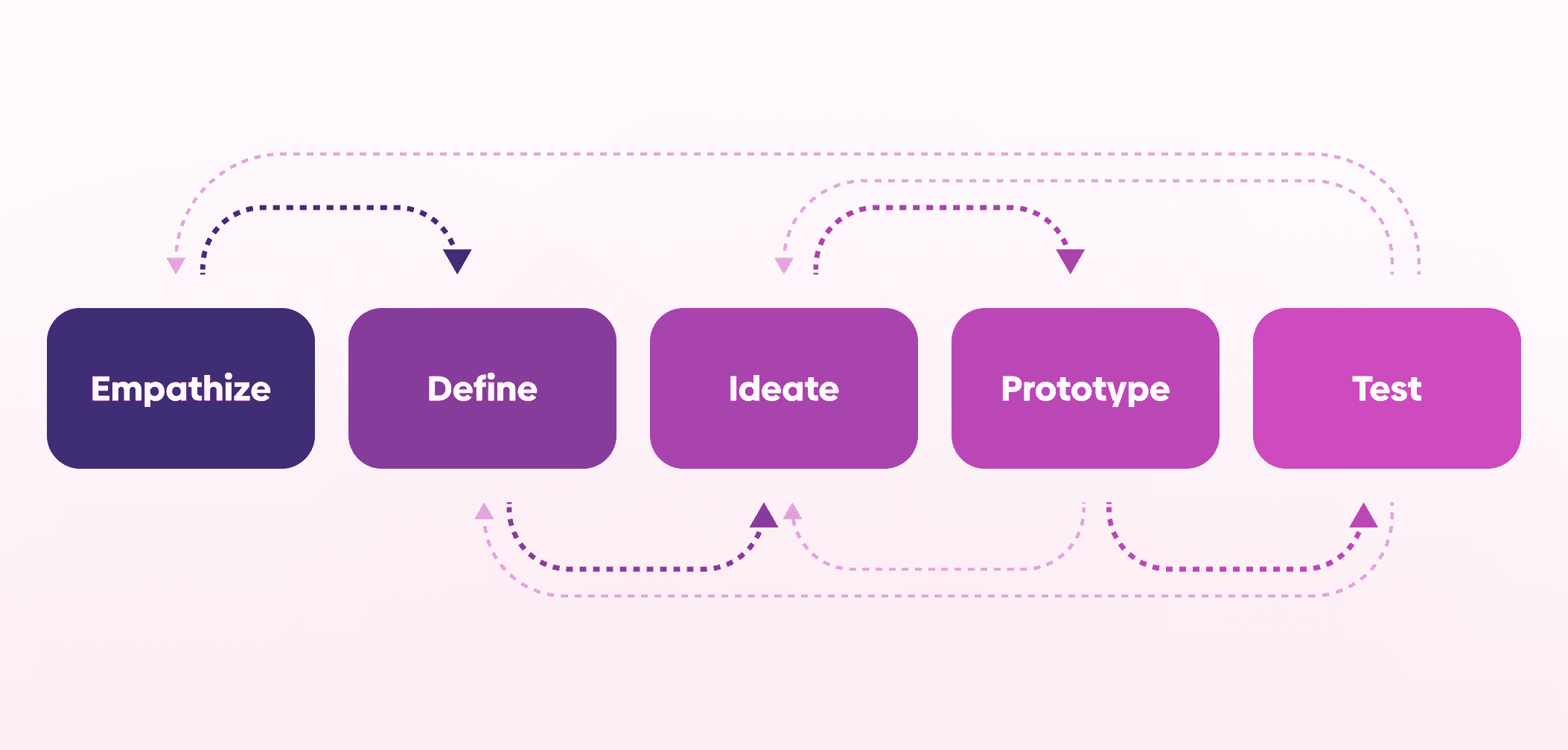

The five stages of design thinking are:

Empathize

Define

Ideate

Prototype

Test

Let’s go through them.

Design thinking is a problem-solving approach built on creating empathy with users, generating ideas, prototyping, and testing those prototypes with the target audience.

The goal is to create solutions that are useful, feasible, and sustainable. It’s an iterative, non-linear process where we don’t get attached to ideas and quickly adapt based on feedback.

Design thinking makes concepts and methods familiar to designers more accessible to non-designers, and it can be used to solve any type of problem — even those where the outcome isn’t a digital product. It’s an open, flexible, iterative, interdisciplinary, and user-focused methodology.

Design thinking is especially useful for confusing or unknown "wicked" problems, a concept introduced by Horst Rittel in the 1960s and formalized with Melvin Webber in their 1973 paper. Wicked problems are messy, complex problems with no single right answer, which later became essential to design thinking.

Modern design thinking has roots in 20th-century developments in design methods, systems thinking, and management science, especially in response to complex post-war technological and organizational challenges.

In 1992, Richard Buchanan linked design thinking and wicked problems, positioning design thinking as a way to merge knowledge from separate, specialized disciplines.

In 2004, David Kelley co-founded the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford, commonly known as the d.school, making design thinking a central practice in education and innovation.

Today, design thinking is widely used in universities, business schools, and companies as a leading innovation methodology.

The five stages of design thinking are:

Empathize

Define

Ideate

Prototype

Test

Let’s go through them.

There are five commonly used stages of design thinking, and teams often cycle between them as new insights appear. Let's go through them all.

The first stage of design thinking is building empathy. This is a stage where you focus on understanding users' needs and challenges. It requires thorough research into users’ habits, expectations, needs, and pain points. It also helps us step away from our own assumptions and redirects us toward the real problems of real users.

In this stage, you focus on clarifying the problem and the underlying needs. This is the stage where you decide which problem should be solved and why. The define stage narrows our focus from multiple potential problems to the one(s) that, based on the collected insights, appear most relevant.

This stage of design thinking is where you focus on ideating potential solutions. The goal is to generate as many creative ideas as possible using various creative-thinking techniques such as brainstorming, hot potato, reverse thinking, and more. In this stage, you explore a wide range of ideas without limitations. The ideas you come up with don’t need to be “good” or “perfect” at this point.

In the prototype stage, you will start prototyping solutions for your problem statement. You should create the prototypes as quickly and cheaply as possible so that you can test ideas easily and with minimal risk. If an idea doesn’t work, you return to one of the previous stages of the design thinking process.

In the final stage of the design thinking process, you will test the prototype with the target audience. Depending on the results, you can then return to any of the previous stages or move forward into solution development.

For a step‑by‑step example on the product design process, see our Product Design Process Simplified article.

Design Sprint:

Time-boxed

Focused on rapid iteration

Suited for a specific type of problem

Linear process

Well-suited for startups

Time-boxed

Focused on rapid iteration

Suited for a specific type of problem

Linear process

Well-suited for startups

Design Thinking:

Not time-restricted

Can be applied by non-designers in many different contexts

Non-linear process

Used across a wide range of industries and organizational types

Not time-restricted

Can be applied by non-designers in many different contexts

Non-linear process

Used across a wide range of industries and organizational types

There are several pain points when it comes to design thinking. Let's go through them!

No-progress workshops happen when you do design thinking activities, but nothing actually gets decided, and nobody owns the next steps. So the question is, how do you spot it? Here are some red flags that can help you spot a no-progress workshop.

Clarity problems: The problem statement keeps changing, activities feel like random games, and there are no clear success criteria.

No prioritization: There are 50 ideas; all are interesting, but none are selected or discarded.

Output ≈ input: You leave the workshop with the same assumptions and options you walked in with, just better documented.

Clarity problems: The problem statement keeps changing, activities feel like random games, and there are no clear success criteria.

No prioritization: There are 50 ideas; all are interesting, but none are selected or discarded.

Output ≈ input: You leave the workshop with the same assumptions and options you walked in with, just better documented.

These are just some of the red flags that you might spot during no-progress workshops. They usually don’t happen because people are lazy or don’t care. No-progress workshops happen because of how the workshop is set up in the first place. You can think of them as a symptom, not the root problem.

You might be wondering how to fix them. There are a few things you can do to ensure they don't become a no-progress workshop. You can:

Define a concrete goal: Replace vague goals with specific outcomes.

Check if the "right" people attended.

Use checkpoints halfway through. You can ask simple, quick questions, such as "What have we actually decided so far?"

Define a concrete goal: Replace vague goals with specific outcomes.

Check if the "right" people attended.

Use checkpoints halfway through. You can ask simple, quick questions, such as "What have we actually decided so far?"

If, on the other hand, you are already a few hours in and you can see that it’s going nowhere, try suggesting a pause to summarize what you've come up with. And remember, you don’t have to be the facilitator to help.

If you want concrete tips on structuring better sessions, read our guide on how to run a UX workshop.

Solution bias is when you jump to a favorite feature before understanding the real problem. You can spot it in the way problems are framed, in team behavior and conversations, and even in deliverables. Solution bias can also happen when you're feeling under pressure. So, how do you fix it?

It's important you reframe how problems are defined, separate problem-space and solution-space, and explore more than one solution on purpose. Solution bias thrives when there’s only one idea on the table. To get more ideas you can run a crazy 8s or rapid ideation exercise. Doing that won’t slow you down much, but it will massively increase the chance you pick something worthwhile.

So, next time you’re in a project review, ask yourself:

Can we state the problem clearly without naming the solution?

Do we have evidence that this is a real problem (user quotes, data, observations)?

Have we considered at least 2–3 different solutions?

Have we listed our riskiest assumptions and decided how to test them?

Are our success metrics about user/business outcomes, not just feature usage?

Can we state the problem clearly without naming the solution?

Do we have evidence that this is a real problem (user quotes, data, observations)?

Have we considered at least 2–3 different solutions?

Have we listed our riskiest assumptions and decided how to test them?

Are our success metrics about user/business outcomes, not just feature usage?

If you’re saying “no” to several of these, you’ve probably got solution bias.

Faux empathy in design thinking is when personas and insights are made from opinions and assumptions instead of real user input. It may appear as rushing into solutions without a deep understanding, using tools like personas in a thoughtless way, or mistaking empathy for a guaranteed path to good design.

So, why does it happen? It mostly happens because of constraints and human psychology, not bad intentions. And to fix it you don’t need a giant UX research function. You need small, consistent changes that tie empathy to evidence.

To fix faux empathy, try:

Marking what’s real versus what’s assumed

Making user contact small and frequent

Building personas from evidence, not imagination

Including “proof of empathy” in your templates

Marking what’s real versus what’s assumed

Making user contact small and frequent

Building personas from evidence, not imagination

Including “proof of empathy” in your templates

Over-polished prototypes are another pain point that can occur in the design thinking process. It happens when you spend the time perfecting visuals or solutions instead of learning fast.

You can spot them in the work itself; for example, when prototypes look like finished products, there are tons of screens and edge cases, or when people resist altering flows.

Why do over-polished prototypes happen? Sometimes it’s about feeling proud, and “ugly but smart” work feels risky to show. Other times it can be because of a misunderstanding of what prototypes are for. There's also the fear of looking sloppy or unprofessional in front of users or leadership.

So, how do you fix this pain point?

Start with learning goals, not aesthetics: fidelity should be just high enough so that users can respond to the idea.

Create prototype constraints on purpose: they should force focus on structure, flow, and concept.

Align expectations with stakeholders and devs: it reduces the pressure to make it perfect and reminds everyone of the goals.

Start with learning goals, not aesthetics: fidelity should be just high enough so that users can respond to the idea.

Create prototype constraints on purpose: they should force focus on structure, flow, and concept.

Align expectations with stakeholders and devs: it reduces the pressure to make it perfect and reminds everyone of the goals.

Have you ever found yourself asking questions instead of watching people try tasks? Don't worry, it happens way more than you would think. Testing opinions instead of behaviors is the next design thinking pain point on our list. It happens when you're relying on what people say they’ll do (“Would you use this?”) instead of watching what they actually do when you give them a real task.

So, why does it happen? First, because it’s quite easy to ask questions, and oftentimes stakeholders prefer big, simple numbers, such as "80% of people said yes". But, by doing that we sometimes forget about human psychology, and how more often than not, testers might want to be polite, helpful, and not look foolish, or they say “Yes, I’d use this” because it costs them nothing.

To fix this, you have to shift your mindset. Use opinions to explain behavior, not to replace it. Behavior should be your source of truth.

You can try these:

Start with behavior‑based learning goals: If the question is about doing, your research should involve watching doing.

Design tasks, not talk tracks: You can still ask follow‑ups, but after you’ve seen the behavior.

Change how you ask questions: This reduces fantasy answers and anchors people in real life.

Start with behavior‑based learning goals: If the question is about doing, your research should involve watching doing.

Design tasks, not talk tracks: You can still ask follow‑ups, but after you’ve seen the behavior.

Change how you ask questions: This reduces fantasy answers and anchors people in real life.

Testing with convenient people who aren’t your target users is the next pain point we're going to cover. This means testing with whoever’s easy to get (colleagues, friends, random users) instead of the people who actually have the problem you’re designing for. You’re doing research — but with people whose feedback can quietly steer you in the wrong direction.

You can spot it in how you recruit. If you ask “What makes someone a good fit for this study?” and the answer is “eh, basically anyone,” you’re in convenience sampling land.

Another issue shows up in who actually attends the sessions. If you have to do a lot of explaining so the person can “play the role” of your user, they're probably not your user.

Testing with the wrong participants happens because of many factors. Recruitment can be hard, there is time and delivery pressure, or sometimes even social and political constraints.

To fix it, remember that it's better to have a few right participants than a lot of convenient ones. Wrong participants can give you confidently wrong directions.

Define who the “right” participants are: Who they are, what they do, any context or tools needed.

Use colleagues as pilots, not as true participants: Think of internal tests as pre‑flight checks, not the actual flight. Just remember to treat it honestly.

Define who the “right” participants are: Who they are, what they do, any context or tools needed.

Use colleagues as pilots, not as true participants: Think of internal tests as pre‑flight checks, not the actual flight. Just remember to treat it honestly.

Stalling on iteration means you talk to users, collect insights, maybe make a beautiful research deck… and the product basically stays the same.

There are some signs that could help you spot it. Sometimes it's that design v1 and v2 look almost identical, and sometimes it's the same issues that keep showing up across rounds.

There are also a few reasons stalling on iteration happens.

Sometimes it’s the process itself. Research happened too late, roadmaps are locked to features and dates without iteration step between. Other times it’s sunk cost, unclear ownership, or fear of rework.

To fix this pain point, try:

Planning for iteration on purpose

Turning insights into decisions and actions

Keeping fidelity low until you’ve iterated

Aligning expectations

Be honest when you can’t change things, because sometimes you truly have no room to iterate

Planning for iteration on purpose

Turning insights into decisions and actions

Keeping fidelity low until you’ve iterated

Aligning expectations

Be honest when you can’t change things, because sometimes you truly have no room to iterate

Design thinking isn’t just a trend. It shows up in research as a repeatable way to innovate, surface hidden problems, and de-risk what you build. Design thinking fosters innovation and treats it as a structured process, not a random brainstorming session.

Design thinking gives teams a repeatable innovation system instead of relying on random “genius ideas.” It also helps discover creative solutions because it encourages "what if" thinking. Design thinking doesn’t just give you more ideas. It gives you structured ways to get to different and better ideas.

Design thinking helps teams find the unknown — the “wicked” problems. Since it begins with empathy and discovery, not requirements, teams go out to observe, interview, and map the context before deciding what the problem is.

It also encourages reframing by shifting from “How do we build X?” to “What’s really going wrong for people here?” Design thinking is valuable when you don’t know what the real problem is yet. It helps teams discover and frame those problems before they commit to solutions.

Design thinking also reduces product risk by prototyping and testing assumptions early with real users. This prevents teams from over-investing in the wrong thing.

Design thinking frameworks are essentially different maps of the same territory. They look different, but they’re all trying to structure the same core behaviors.

There is no single definition of design thinking—IDEO, for example, describes it as a set of mindsets and activities rather than one fixed recipe

Simply put, you’ll see different diagrams and vocabulary, but they’re all expressing a human-centered, iterative way of working and not a fixed recipe.

Even though there are many different frameworks, they all circle around the same activities. You’ll repeatedly see:

Empathy for users

Reframing the problem

Analyzing and synthesizing insights

Creating and testing prototypes

Iterating based on what you learn

Empathy for users

Reframing the problem

Analyzing and synthesizing insights

Creating and testing prototypes

Iterating based on what you learn

A design thinking mindset is less about memorizing a process and more about how you show up to problems — your attitudes, defaults, and everyday habits.

Be empathetic: Stay in regular contact with real users, use simple empathy tools, listen before solving, and reflect as a team.

Be collaborative: Co-create instead of presenting, rotate roles in workshops, share raw work early, and make collaboration visible.

Be optimistic: Use “Yes, and…” in ideation, treat constraints as design briefs, celebrate learning (not just wins), and model realistic optimism.

Embrace uncertainty: Write provisional problem statements, make assumptions explicit, and normalize “We don’t know yet.”

Be curious: Ask “Why?” often, do small field visits or observations, and reward good questions in meetings.

Embrace diversity: Build cross-functional teams, invite non-usual voices, and check diversity for every project.

Run experiments and learn from them: Make decisions based on evidence, not opinions.

Be empathetic: Stay in regular contact with real users, use simple empathy tools, listen before solving, and reflect as a team.

Be collaborative: Co-create instead of presenting, rotate roles in workshops, share raw work early, and make collaboration visible.

Be optimistic: Use “Yes, and…” in ideation, treat constraints as design briefs, celebrate learning (not just wins), and model realistic optimism.

Embrace uncertainty: Write provisional problem statements, make assumptions explicit, and normalize “We don’t know yet.”

Be curious: Ask “Why?” often, do small field visits or observations, and reward good questions in meetings.

Embrace diversity: Build cross-functional teams, invite non-usual voices, and check diversity for every project.

Run experiments and learn from them: Make decisions based on evidence, not opinions.

It's not 'us versus them' or even 'us on behalf of them.' For a design thinker, it has to be 'us with them'

Tim Brown, co-founder and CEO of IDEO

It's not 'us versus them' or even 'us on behalf of them.' For a design thinker, it has to be 'us with them'

Tim Brown, co-founder and CEO of IDEO

Design thinking isn’t magic—it’s a structured way to stay close to users, frame problems clearly, and reduce risk before you ship. When you understand the stages, common pitfalls, and shared patterns across frameworks, it stops being a buzzword and becomes a practical tool.

Treat it as an ongoing mindset rather than a rigid process, keep looping between learning and making, and you’ll get more confident, evidence-based decisions out of your team.

We’re thrilled to invite you to join our incredible community of product designers (and enthusiasts) by following us on Instagram. We’re here to support you on your journey to falling in love with product design and advancing your career!

Keep on designing and stay hungry, stay foolish! 🥳

We’re thrilled to invite you to join our incredible community of product designers (and enthusiasts) by following us on Instagram. We’re here to support you on your journey to falling in love with product design and advancing your career!

Keep on designing and stay hungry, stay foolish! 🥳

LIMITED-TIME OFFER

Just tell us where to send them

You can unsubscribe at any time—no strings attached

LIMITED-TIME OFFER

Just tell us where to send them

You can unsubscribe at any time—no strings attached